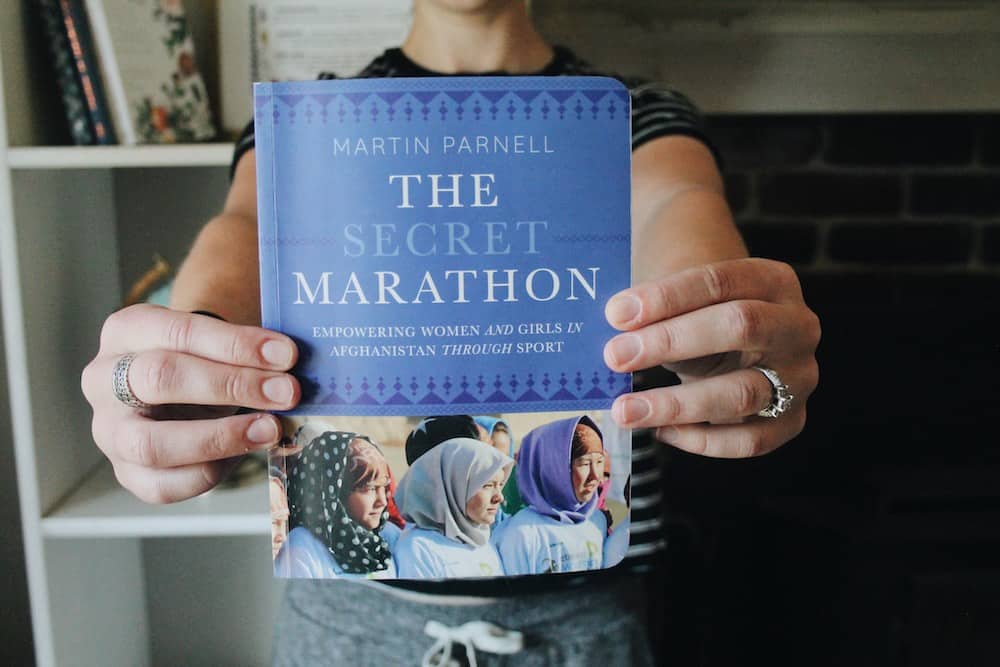

Book Review | The Secret Marathon by Martin Parnell

by Nikki Parnell — April 22, 2020

*Martin Parnell, while we like him and his name, is not related to us in any way that we know of.

Perspective shift. That is what this book will offer you, humbly, as it opens your eyes to the running scene in a far away corner of the world. After reading, I have a new found appreciation for the freedom and safety that I’ve always had as a woman to run and play sports as much or as little as I want. Growing up in a safe town in the USA, the only true limiting factor to my running has been myself. There are the precautions everyone should take when running, like being aware of the people around you or potential wildlife in the area, but the majority of threats I’ve felt to my physical wellbeing have been the normal self–inflicted mishaps like rolling an ankle, getting sun burnt, running out of nutrition, or chaffing — first world problems.

In this story, the consequences of running are much greater.

Let’s start at the beginning. This is a story of a man and his film crew embarking on an adventure to Afghanistan to run a marathon for women’s rights. The author, Martin Parnell, was 62 at the time of this writing, only having started running at age 47. He is charismatic and keeps setting bucket list goals and endurance quest challenges –- case in point, he once ran 250 marathons in a year! He uses his running for good by fundraising for non-profits like Right to Play and Free to Run that bring play and sport to areas of conflict or crisis. He set out on this precarious journey to Afghanistan after reading a story about a girl named Zainab, who was the first girl to run a marathon in Afghanistan. He was inspired by her perseverance at overcoming obstacles in a country full of them. At a time where Martin had his own obstacles to overcome – recovery from a life threatening blood clot – he decided to train for the Marathon of Afghanistan and make a documentary to show the world how important the fight for gender equality is in conflict zones. He made the trip, ran the race, wrote this book, did a TedX talk and has since put on a yearly race in Canada to raise funds for Free to Run.

Martin’s film partner in all of this was Kate, a Canadian woman who agreed to train for the Marathon of Afghanistan too, which would be her first marathon ever. She brought a relatability to the storyline as she shared her personal reasons for why she runs and her trepidation of surviving the marathon distance. Kate runs for mental health and battles a long time addiction to self-harm with running. She tries to outrun her demons and has an overactive mind with negative thoughts pulling her down, “I can’t do this anymore, nothing I do matters, I’m all alone.” Running is her therapy. She says girls like Zainab, “made me think about all the times I had run searching for freedom. Not freedom from inequality, terrorists or landmines – mental freedom.”

Overcoming Barriers

In some sense, this book is about barriers. For Martin, they were largely logistical. Barrier #1: At the time of this writing, the Canadian government had Afghanistan on the “avoid all travel” advisory list along with places like Iraq, Somalia, North Korea, and Syria. Barrier #2: Martin and his crew had to find life insurance that covered things like, “kidnapping, dismemberment, terrorism, and death.” Barrier #3: There were some difficulties getting Martin’s travel visa, which arrived just five hours before his plane departed! Barrier #4: There is a great sacrifice to go into a place that is so unstable; it makes it difficult to say goodbye to loved ones. You hope everything will be fine… but what if?

Then there are the gender barriers against women in Afghanistan. This is a country where women don’t play sports. If you are a woman and are challenging the status quo by running, depending on where you are in the country, people may throw things at you, harass you and call you terrible names, try to run you off the road with their car or bike, tell you they HATE you for running a race and that you are destroying Islam. Because the streets are often unsafe for girls to run in, they are forced to train on treadmills, run circles around their fenced gardens, or wake up and run on the streets or trails at 2am when not many people are out. One girl, Nelofar, said, “I had come to expect the greater society’s anger at me for running… Afghanistan is a country where you do not see many women, not only in running or other sports, but anywhere.” Women are not seen. How do you make the invisible, visible?

Taylor Smith, who works for Free to Run, wrote in an excerpt, “Did the women in this region know what they were missing? Yes, they knew. And no, they wouldn’t stand for it any longer… Afghanistan is not a country that is ready to see women out jogging in the streets, even with a male chaperone. But the women of Afghanistan are ready. And who are we to deny them the freedom to be who they want to be?” The problems and barriers to women running aren’t going anywhere, but neither are these women who are fighting to be free.

Marathon Day in Bamyan, Afghanistan

Let’s fast forward to the race. It took place in Bamyan, which has a large Hazara population. The Hazara are Shia, so the region is culturally unique from the rest of Sunni Afghanistan, which is more conservative. It better tolerates men and women running together than in other parts of the country. Martin illustrates Bamyan as a town I would love to see. It’s at high elevation in a valley with natural beauty all around. It backs up to the Hindu Kush mountain range, has stunning rock outcroppings and big cliff walls with hundreds of caves carved throughout. Many people call those caves home and kids even go to school in them. Bamyan is a place drenched in history. Back in the time of the Silk Road, it was a Buddhist hub and a major trading site during the 1st-8th centuries. This is the site of the Big Buddhas, two Buddha statues 35 and 53 meters tall, carved into the sandstone cliffs between the 3rd and 6th centuries. Now, it looks more like a giant excavation site because the Taliban blew them up in 2001. One of the race organizers, James Wilcox, described Bamyan, “as a place apart, hidden by mountains, a bubble of peace and calm in a sea of trouble. The fact that a mixed-gender marathon can even be held in Afghanistan is a testament to Bamyan’s unique character.” He wants to bring people to Afghanistan, “not because it is broken but because it is beautiful.”

No matter what, you have to be brave to partake in this event. Kate explains they, “were told about the route only a week before the event and were sworn to secrecy to avoid being targeted by terrorists… Armed guards lined the entire route and National Defense Service trucks followed closely behind each female runner, reminding us that this is a country still very much at war.”

A big takeaway for me was the reminder of how important men are in changing this country’s view on women running and participating in sport. From fathers that support women being educated, independent people to the men who lined up next to the women in the race. Men have to show the country and the world that they stand in support of these women if real change and equality is going to happen. One of the runners, Zahra, said about the race, “I was happy about the fact that people from different genders were competing against each other. We were looking at each other not through our genders, but through a different lens, that of humanity.” This race gave her the opportunity to see her country transform and she glimpsed its potential while running through it.

Kate finished the marathon, which was her first marathon ever, hand in hand with an Afghan man and an American man (not directly holding hands with the Afghan man because that would break tradition). Afghan men are often feared because they’re associated with the terrorists that have wreaked havoc on the country for so long, but these two men were there for Kate with encouragement in the tough spots of the race. After the race, Kate said, “I came into this race scared that I would not be able to face down my own mental health struggles, and I emerged with a reassurance that I would not be left alone to face them.”

Martin ended up running the race with a girl named Kubra who hadn’t been able to train for the marathon due to a traumatic bombing incident at her school. But it meant so much for her to try so Martin ran every step of the way with her and they finished under the cutoff time.

Running has a way of uniting people. Racing lends a community the chance to gather and work towards a common goal. In fragile places like Afghanistan, where turmoil is often the focus, I felt such a sense of relief and elation that the race was able to take place, that it went smoothly and that it could serve as a concrete example of how women and men can run alongside one another. Each year that the race takes place is another victory and step forward towards progress and equality.

Fight the Good Fight

This book often reads like a documentary. It cuts to different scenes and different people’s perspectives, which I appreciate. You get to see “behind the scenes footage” and hear from the race directors, organizers, Free to Run workers, the girls who ran the marathon, and others. Each person plays a unique roll in telling this story. At times, the book also reads like Martin’s journal, including some dry play-by-play details that at times feel monotonous but help paint the overall picture of the events that transpired. This is an important book with an essential message for the world. By writing this book, a light is shone on a place outsiders have always seen as dark. It’s good to see the beauty. It’s good to know the hardships. It’s good to think about people outside of our own running communities. It’s good to see how brave and unstoppable the human spirit is, especially in these women and girl runners in a country with all the odds stacked against them.

Martin and the many other characters in this book dropped me on the war torn streets of Afghanistan to walk a mile in the shoes and under the hijabs of the courageous women and girls who continually fight for their basic right to run. Danger lurks everywhere. But the desperate need to be free and equal outweighs the risks, and so the girls keep running – vulnerable, hated at times for their passion, but moving forward and not taking no for an answer.

Get your copy of The Secret Marathon through the publisher, Rocky Mountain Books.

We Need Your Help.

If you found value in this article, consider supporting Treeline Journal through Patreon for as little as $2 a month. Every little bit goes a long way!